Grigori Rasputin

Grigori Rasputin

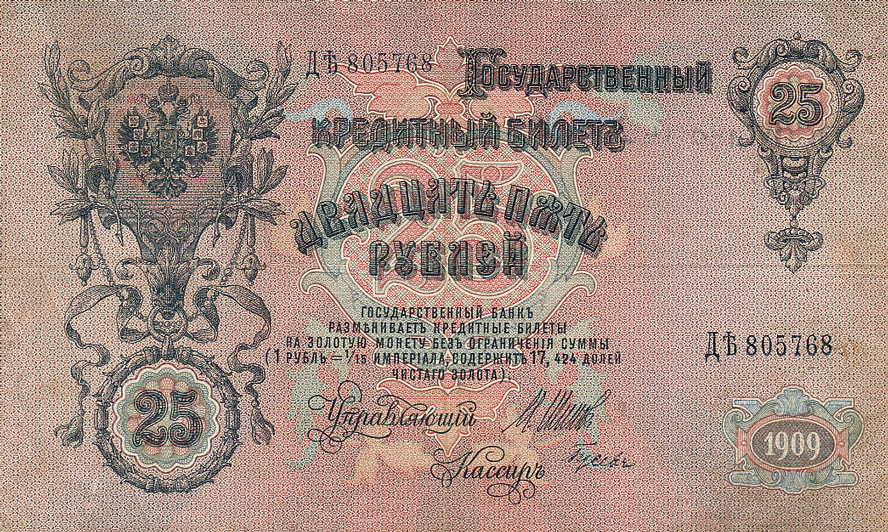

Signed Russian Ruble Banknote - 1909

A curious piece of history from Russia’s stormy political past — a beautiful 25 Ruble banknote, dating from Tsarist Russia in 1909, and signed by the Mad Monk himself, Rasputin. This banknote features Tsar Alexander III, who on his death was succeeded by his son Nicholas II as Emperor of Russia, and whose patronage enabled Rasputin to gain an unlikely position of influence in Tsarist Russia. Above Rasputin’s pencil signature is the ink notation in Russian that translates as, “The signature of Rasputin.” The notation was made by the original Swiss collector who obtained it from Rasputin around the turn of the century.

We have acquired several authentic historical items from this particular late 19th-century collector’s estate in Switzerland, and are no longer surprised by such notations on his memorabilia (you can find similar exclamations on another Rasputin item we sold, as well as Geronimo and Chief Rain-in-the-Face); a Letter of Provenance will be furnished to interested buyers.

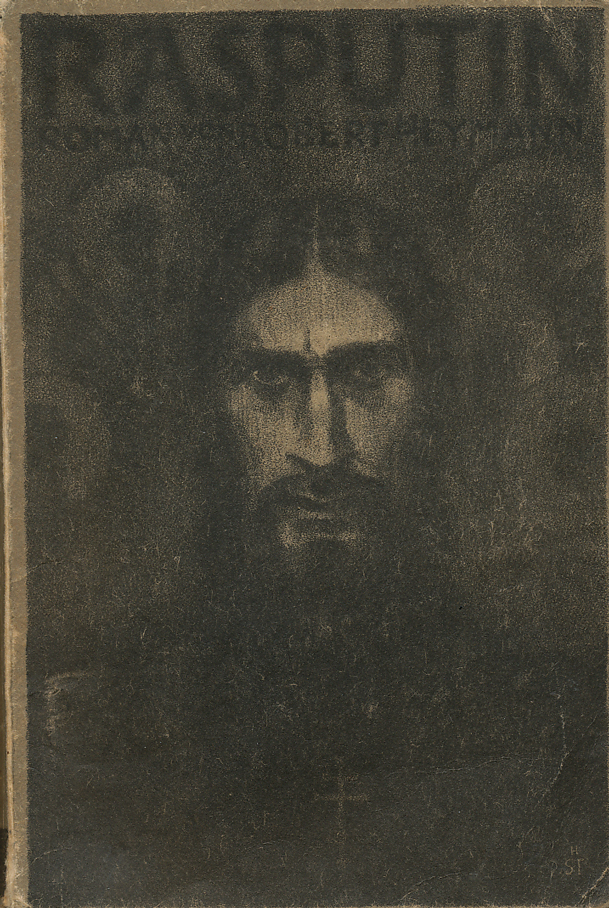

Also accompanied by a small format 180-page book about Rasputin published in German in 1917, and a Russian postcard from the era, unused, with a typed note in German on the back (the content of which will be provided to interested buyers, as it is culturally sensitive).

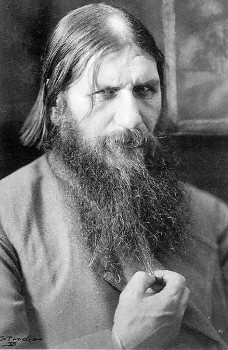

GRIGORI YEFIMOVICH RASPUTIN (1869-1916) was a Russian mystic who is perceived as having influenced the later days of the Russian Tsar Nicholas II, his wife the Tsaritsa Alexandra, and their only son the Tsarevich Alexei Nicholaievich. Rasputin had often been called the “Mad Monk,” while others considered him to be a psychic and faith healer. There has been much uncertainty over Rasputin’s life and influence, for accounts of his life have often been based on dubious memoirs, hearsay, and legend.

Rasputin was born a peasant in the small village of Pokrovskoye, in Siberia. Not much is known about his childhood, but the myths surrounding Rasputin portray him as showing indications of supernatural powers throughout his childhood.

When he was around the age of eighteen, he spent three months in the Verkhoturye Monastery, possibly a penance for theft. His experience there, combined with a reported vision of the Mother of God on his return, turned him towards the life of a religious mystic and wanderer. It also appears that he came into contact with the banned Christian sect known as the khlysty (flagellants), whose impassioned services, ending in physical exhaustion, led to rumors that religious and sexual ecstasy were combined in these rituals.

Rasputin married Praskovia Fyodorovna Dubrovina in 1889, and they had three children, named Dmitri, Varvara, and Maria. Rasputin also was thought to have fathered at least one other child by another lover. In 1901, he left his home in Pokrovskoye as a pilgrim and, during the time of his journeying, travelled to Greece and Jerusalem. In 1903, Rasputin arrived in Saint Petersburg, where he gradually gained a reputation as a staryetz (holy man) with healing and prophetic powers.

In 1905 the young Tsarevich sustained a bruise after falling off a horse. A hemophiliac, the young Alexei suffered internal bleeding for days. His mother, Alexandra, asked a close friend, Anna Vyrubova, to secure the help of the charismatic monk Rasputin. Word had reached the royal court that Rasputin was said to possess the ability to heal through prayer, and he was indeed able to give the boy some relief, in spite of the doctors’ prediction that he would die. It was said that every time the boy had an injury that caused him internal or external bleeding, the Tsaritsa called on Rasputin, and Alexei subsequently got better-making it appear that Rasputin was effectively healing him.

It wasn’t long after that Tsar Nicholas referred to Rasputin as “our friend” and a “holy man,” a sign of the trust that the family placed in him. Rasputin had a considerable personal and political influence on Alexandra, and the Tsar and Tsaritsa considered him a man of God and a religious prophet. Everyone desirous of an audience with the royal couple had to go through him, a situation that angered certain individuals. Alexandra came to believe that God spoke to her through Rasputin.

Rasputin soon became a controversial figure, becoming involved in a paradigm of sharp political struggle involving monarchist, anti-monarchist, revolutionary and other political forces and interests. Though while fascinated by him, the Saint Petersburg elite did not widely accept Rasputin: he did not fit in with the royal family, and he and the Russian Orthodox Church had a very tense relationship.

While Tsar Nicholas was away at the front during World War I, Rasputin’s influence over Tsaritsa Alexandra increased immensely. He soon became her confidant and personal adviser, and also convinced her to fill some governmental offices with his own handpicked candidates. To further the advance of his power, Rasputin cohabited with upper-class women in exchange for their granting him political favors. Because of the war and the ossifying effects of feudalism and a meddling government bureaucracy, Russia’s economy was declining at a rapid rate. Many at the time laid the blame with Alexandra and, because of his influence over her, with Rasputin as well.

The legends recounting the death of Rasputin are perhaps even more bizarre than his strange life. His murder has become legend, some of it invented by the very men who killed him, which is why it becomes difficult to discern exactly what happened.

It is, however, generally agreed that, on December 16, 1916, having decided that Rasputin’s influence over the Tsaritsa had made him a far-too-dangerous threat to the empire, a group of nobles, led by Prince Felix Yusupov and the Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich (one of the few Romanov family members to escape the annihilation of the family during the Red Terror), apparently lured Rasputin to the Yusupovs’ Moika Palace, where they served him cakes and red wine laced with a massive amount of cyanide. According to legend, Rasputin was unaffected, although Vasily Maklakov had supplied enough poison to kill five men.

Determined to finish the job, Yusupov became anxious about the possibility that Rasputin might live until the morning, which would leave the conspirators with no time to conceal his body. Yusupov ran upstairs to consult the others and then came back down to shoot Rasputin through the back with a revolver. Rasputin fell, and the company left the palace for a while. Yusupov, who had left without a coat, decided to return to grab one, and, while at the palace, he went to check up on the body. Suddenly, Rasputin opened his eyes and lunged at Prince Yusupov. When he grabbed Prince Yusupov he ominously whispered in Yusupov’s ear, “You bad boy!” and attempted to strangle him. As he made his bid to kill Yusupov, however, the other conspirators arrived and fired at him. After being hit three times in the back, Rasputin fell once more. As they neared his body, the group found that, remarkably, he was still alive, struggling to get up. They clubbed him into submission and, after wrapping his body in a sheet, threw him into an icy river, where he finally met his end.

Three days later, the body of Rasputin, poisoned, shot four times and badly beaten, was recovered from the Neva River.

All Vintage Memorabilia autographs are unconditionally guaranteed to be genuine. This guarantee applies to refund of the purchase price, and is without time limit to the original purchaser. A written and signed Guarantee to that effect accompanies each item we sell.